The Arrow

Resolving the mystery surrounding one of Willie Crowther's greatest hits

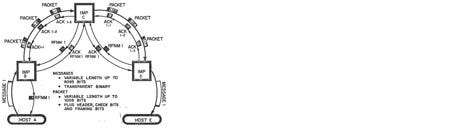

Before the Internet, there was the Arpanet, and before the Arpanet, there was a cluster of machines, called IMPs, for Internetworking Message Processors. The idea was, it was hard to get all the different mainframe and minicomputers to communicate with one another. So there would be another machine, the IMP, which IBM would figure out an interface to, and Sperry Rand would figure out an interface to, as would Digital Equipment, and so on. The IMPs were designed with software that would allow them to talk to each other: IBM 360 /\ IMP < - - - > IMP /\ Univac, where the /\ is a custom interface for exchanging packets of data:

Image: ResearchGate

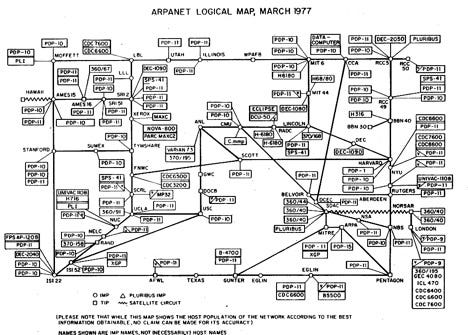

And so a grid could be created with IMPs talking to each other in the center and all of the disparate mainframes on the periphery, each connected to its IMP. This was what the early Arpanet looked like, courtesy of Wikipedia:

The DoD Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) contracted with a Cambridge, Mass., company, Bolt, Beranek, & Newman (BBN, still around but now owned by Raytheon) for the IMPs. Both Bolt and Beranek were MIT professors (Newman joined a bit later) and the first offices were on the MIT campus. As could be expected, MIT grad students contributed to this early work, including a young computer scientist named Willie Crowther.

I once tried to write an article on why so many rock climbers are scientists and engineers. Being a Gunks climber, I had in mind Wiessner (chemist); Shockley, Lester Germer, John Reppy, and John Stannard (physicists); John Gill and Rich Goldstone (mathematicians), and so on, but also that Frost and Jardine were both aerospace engineers. Crowther wasn’t the only computer scientist, but probably the most famous point of intersection with climbing.

In fact, it wasn’t just these famous climbers. Shockley’s co-Nobelist, John Bardeen, also climbed, and for all I know, so did the third in that Nobel trio Walter H. Brattain. All three worked at Bell Labs at the time as would, later, Neil J.A. Sloane, co-author of the climbing guidebook for New Jersey. The other co-author, Paul Nick, is a software engineer. The guy who designed the first New Jersey Rock Gym, in Wayne, N.J., whose name I can’t recall, was a mechanical engineer working as an electrical engineer, or vice versa.

Ted Selker, a specialist in human–computer interaction who designed, among other things, the first trackpoint (the pink rubber button in the middle of a laptop keyboard that was originally created for the revolutionary IBM ThinkPad), once told me that the only reason he even interviewed at IBM was because, while working for a small company in California, he was told about an HCI position at IBM’s Poughkeepie offices. “Wait, isn’t Poughkeepsie right near New Paltz?” he asked them. In other words, he took the interview because it was a free trip to the Gunks.

Anyway, while writing this article (which never got published) I had trouble contacting Willie Crowther at first, because Google kept coming back with references to a Willie Crowther who invented the first adventure game (aptly named "Adventure"). When I finally got ahold of the Internet/rock climbing Willie Crowther, I mentioned that. “Oh,” he said. “That was me too.”

Willie put up three of my favorite routes at the Gunks: Hawk (5.5), Moonlight (5.6), and Arrow (5.8). When I was first going through the grades, which for me were all onsights, I had a lot of trouble finding the second pitch of Moonlight. Wait, I thought to myself, this was done by the same guy who did Hawk, which I had done. Where would the Hawk guy go? As soon as I asked myself that, I saw the long traversing line of the pitch.

Arrow is a puzzle for anyone the first time they climb it, and maybe subsequent times too. My first time, I couldn’t figure out the crux, which is right near the end of the climb and right at a bolt, one of two on the route. There did not seem to be a way to go straight up, at least not a way that I, early in my 5.8 leading, could do. There might be a way to the right, but that looked off-route and not easy. There was also a way to the left, which seemed off-route as well, but not so hard. I finally went that way, convincing myself that if I didn’t go entirely into the lichen, I wasn’t entirely off-route.

There’s always been a question about the bolts on Arrow. First, let me describe the route. A lovely 5.6 pitch takes you to the GT ledge. There, a few tricky-but-not-hard up-and-traversing moves take you to good gear below a tricky and wildly fun 5.6ish roof.

From there, face climbing on stunningly gorgeous white rock takes you to a stance, a bolt, and a tricky 5.7ish crux-ish set of moves, from which you get some more gear and a short, easy runout to the second bolt. The stance there is a little too good, giving you an infinite amount of time to look around and be confused about which way to go (see above). Once you make the crux move (or avoid it by going left or right), you’re only a move or two from a ledge and an all-too-popular also-used-by-neighboring-climbs rap station.

Gunks climbers, of my generation at least, were told the same legend about the bolts: Willie Crowther climbed Arrow without them, but friends told him it was unsafe without at least a couple of bolts, and so he put them in on rappel. That contradicts the black Williams guidebook, which says, “FA 1960: Wilie Crowther and Gardiner Perry, after rappelling down to clean the face and place the bolts.” (The gray guidebook is less committal, saying, “The First Ascent party placed the bolts on rappel,” that is, not saying whether it was before or after the first ascent.) Swain as well says that the bolts were placed “after the first ascent.”

As it turns out, there’s a wonderful thread on Mountain Project that explains everything. After much back-and-forth, someone named Eric Engberg posted “from the ‘mouth’ (keyboard) of the horse” with Crowther’s email response:

1st time up, went around the hard move to the left

To see if it was even possible, went back and did it on top rope. It went but was covered with lichen — a real mess

then cleaned it, bolted it, and led it.

In those days, I wanted any route I put in to be reasonably safe for my friends to lead, and this was a nice route. So yes, bolt it.

Today, most people go somewhat right of the route I found - mine was a pure mantle. The slightly easier route to the right was buried in lichen.

Gardiner Perry was first to spot the line. He tried to lead it, then came back and got me to lead it for him.

So there we have it. In a way, every theory is true. Willie did climb the route without the bolts—but without making the crux move. The route was then cleaned and bolted on rappel—not before the FA, but before it was ever climbed as we do today. Gran’s guidebook, which doesn’t mention the bolts at all, does say, “The final move can be avoided by an escape to the left.”

One final note: Arrow is the only route I’ve ever heard called “The Arrow” and, to my experience, that’s the way just about every climber older than myself refers to it. Apparently, though, it was common back in the day to say, “the X,” even if the route name doesn’t have a “the.” (Some do, e.g., The High Traverse out at Millbrook.) Gran even says, in the intro section of his guidebook, “the Betty.” I asked Dick Williams (born in 1938) about it, and he said, “Hmm, I never noticed that.” Nor had Joe Bridges (born 1939). Just one more cool custom gone by the wayside.

Anyway, if you haven’t ever climbed the Arrow, it’s a must-do. And if you’re confused about the move, don’t ask yourself, What would Willie Crowther do?