My election day: all work and no joy

This wasn’t Harris’s fault. And it wasn’t ours

For months I moaned privately (not privately enough for my partner) about Joe Biden’s decision to run for reelection. Many of us had taken him at his word that he intended his to be a transitional presidency — to put Trump behind us, to restore the rule of law, to repair the economy, to finish the job on Covid, and to hand a better country over to the next generation.

Biden achieved most of that. To be sure, he mismanaged Covid, though not nearly as badly as Trump had, and Gaza, where his vast experience in foreign affairs was a hindrance, blinding him to the ways Netanyahu was playing him. But he wildly exceeded expectations with the IRA and CHIPS. He maneuvered a reluctant nation and a hesitant Europe through the Ukraine crisis, with almost as much boldness as was needed.

I was frankly surprised and pleased. He had maybe outgrown his serial plagiarism, his stutter, his torpedoing of Anita Hill, his racist crime bills, and his lifelong reluctance to support reproductive freedoms.

Yet, Biden is such a poor speaker — both in style and content — that I had never been able to get through an entire speech of his. (He had, to cite just one painful example, barely out-debated Sarah “I can see Russia from my kitchen window” Palin in 2008.) But I made it all the way through the State of the Union, because it was excellent. He was excellent. Still, most of the country clearly didn’t want him to run again.

In February, Ezra Klein put words to our thoughts with an electrifying podcast (“Democrats Have a Better Option Than Biden”) that insisted it wasn’t too late for Biden to step aside after all. Klein acknowledged that the Biden of the State of the Union was up to the job. But would we have that version of Biden for four more years?

Then came the June debate. It turned out, we didn’t even have that version of Biden for four months. Fortunately, this time, he could feel the cold hand of the political grim reaper on his shoulder.

Again Ezra Klein called for some kind of selection process. Again I agreed with him.

But by about a week into the Harris campaign, my usual cynicism was largely replaced by hope and joy. Miraculously, the mainstream media supported her with heroic photography, shooting her from street level, upward. Miraculously, she chose my guy, Walz, instead of my governor. Miraculously, she drew huge crowds and inspired even bigger Zoom congregations — and gobs of small money.

I went all in. Voter registration, including one day at the county jail. Phone banking. Letters to fellow Pennsylvanians. Postcards to western North Carolina.

And a ton of canvassing — two or three times a week. Toward the end, I was a “captain,” helping train and send out canvassers, many of them from safely blue states like California, Illinois, and New Jersey.

And this week, I hung up my baseball cap with three Harris–Walz stickers on its brim, and put on an imaginary non-partisan one. I was a Judge of Elections. It was a long day and the judge has the longest day of anyone.

My nephew had inconveniently scheduled his wedding for the weekend before, so my friend Fred — who would also be a poll worker on Tuesday, in a different district (who and with his wife Ellen would host an election-night watch party afterward) — had to pick up my clear plastic Judge’s tote bag for me.

My poll was at a library in Wilkinsburg, a small town on the other side of Pittsburgh’s east edge. I was there before 6 am, organizing my team to get our machines and paperwork ready to open the doors at 7 am. There was already a long line.

It was my first time at this precinct, but throughout the day, people who had voted there for years said it was more crowded than they had ever seen. In a heavily black neighborhood, it was busier than even 2008, I was told.

It was also my first time as Judge. I made mistake after mistake. None prevented any voter from voting, but they didn’t shorten the lines any. Voters were impatient, but I reminded myself that an extra five- or ten-minute wait was nothing compared to the hours-long waits voters had elsewhere, and it was more important to get everything done right.

New rules concerning mail-in balloting and provisional ballots made for new procedures, additional voter lists to look people up on, and time-consuming additional forms to fill out — most of which had to be done, or supervised and signed off on, by the Judge.

Fortunately, four of my five other team members had been poll workers before, at the same precinct. As well, mine was one of three precincts at the same location. We had one or two Constables for most of the day, and, more importantly, one of the other Judges was smart, experienced, and ready to answer my questions and resolve my confusions.

It was one of those long days where at 1:30 it seemed like it would never end, at 4:30 the afternoon rush began, at 6:30 one of the constables looked at his watch and said we’re nearly done, and at 7:30 I realized that there was some paperwork I could get started even before the closing of the polls at 8:00 pm.

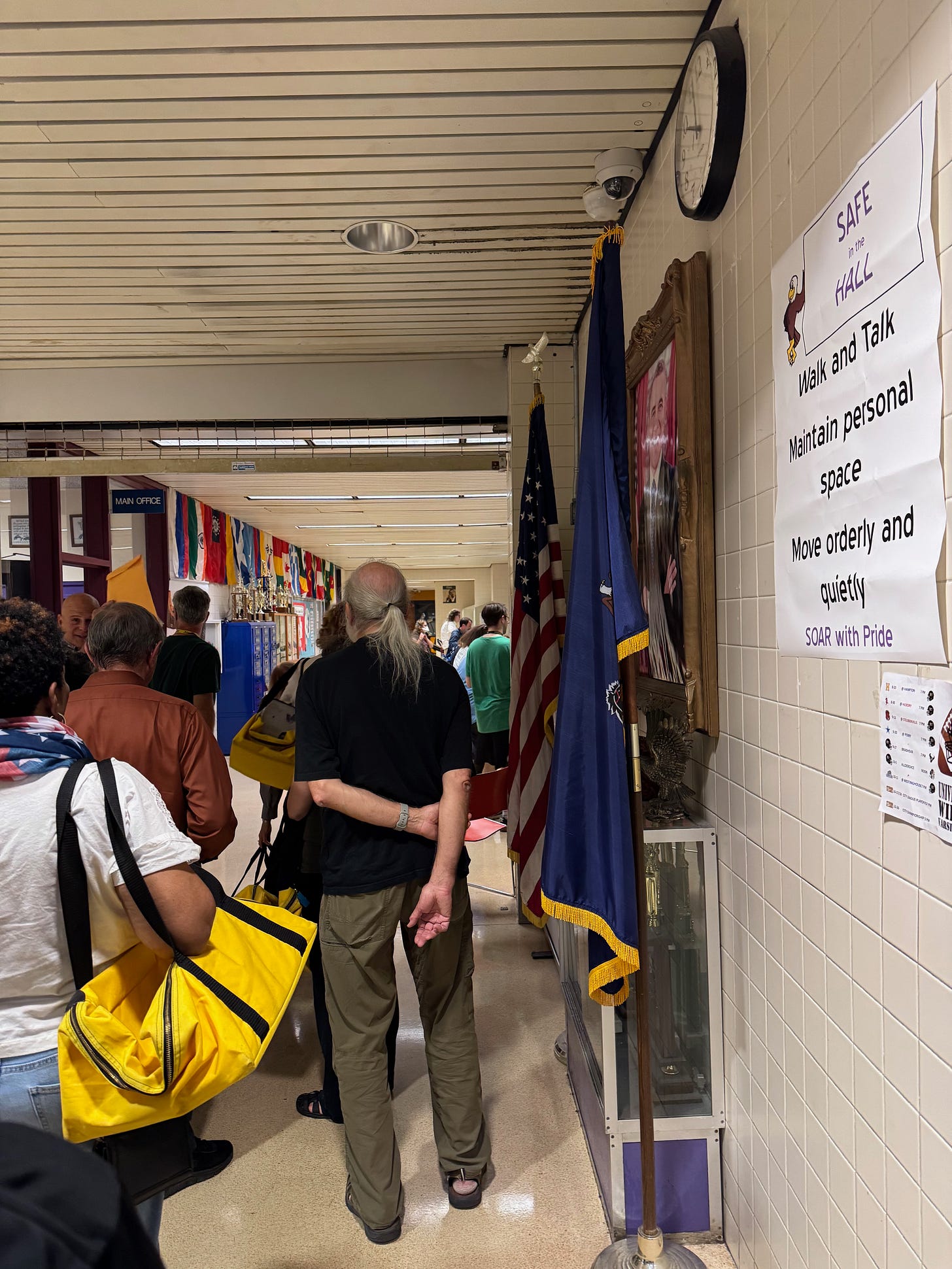

It took me till about 9:10 to get everything shut down and tallied up, and my team out the door. They were done, but I had another hour or so, first getting to the local processing center (a 6–12 grade school about 15 minutes away) and then waiting on a line of fellow Judges that was two corridors long.

There, two workers broke the seals we had placed on my yellow tote full of ballots and an orange plastic bag containing two separate thumb drives and the keys and password to the voting machines. They signed the paperwork that completed the chain of custody for the ballots, paperwork, and equipment. I hadn’t screwed up anything important.

Finally, about 10:30, I arrived at Fred and Ellen’s house, where the seltzer was refreshing, the wine welcome, the results bitter, and the mood glum.

Harris had made mistakes as a first-time presidential candidate, but not as many as I made as a first-time judge. She failed to offer big, easy-to-understand ideas and themes. She failed to break with Biden on Gaza, and she was in no position to break with him on the border or inflation. Failing to break with Biden on anything at all (“Frankly, nothing comes to mind”) was probably the biggest mistake of a campaign that was otherwise remarkably free of them.

I do think that she could have done more to explain inflation. And she got bogged down in the mechanics of what she would do about it, instead of (as her opponent was wont to do) just promising to fix it. She got people worried about reproductive rights, but she didn’t get enough women to the polls to put her over the top. She never tried to get people worried about Social Security, though today, a mere three days after the election, the headlines are focused on it.

Speaking of the headlines, the media deserves a lot more blame than Harris for this loss, and billionaire dark money even more blame than that (most especially in Senate races in Pa., Tx., Mont., and Ohio). I’ll save those thoughts for another time.

I’ll also save for another day any discussion of a shockingly evident lack of understanding of the election’s stakes, candidates, and processes, and some absolutely basic matters of civics and government that go way beyond the failings of the media and take us down a road of schools, literacy, and education finances. I saw it all summer and fall while canvassing; I saw it on NextDoor; and I saw it in my precinct on election day.

Today I want to say I did all I could, and it wasn’t enough. A lot of good people did all they could, and it wasn’t enough. Harris did all she could, and it wasn’t enough.

And to those people who are saying, don’t give up, the fight continues (Elizabeth Warren and Jon Stewart, I’m looking at yinz), I say, f*** you. Winning this election was a piece of cake compared to what it would take to save democracy now, and everything we did wasn’t enough. If you’re not feeling more than a little despair, you’re just not paying attention.