Mike Lee backs down on selling off public lands

But not for the right reasons

Dear Mike,

I’m sorry, but it seems like you still don’t get it. The problem with selling off public lands is not that they might end up in the hands of the Chinese, or BlackRock, or whoever it is you happen to dislike. The problem with selling off public lands is that they will no longer be in public hands.

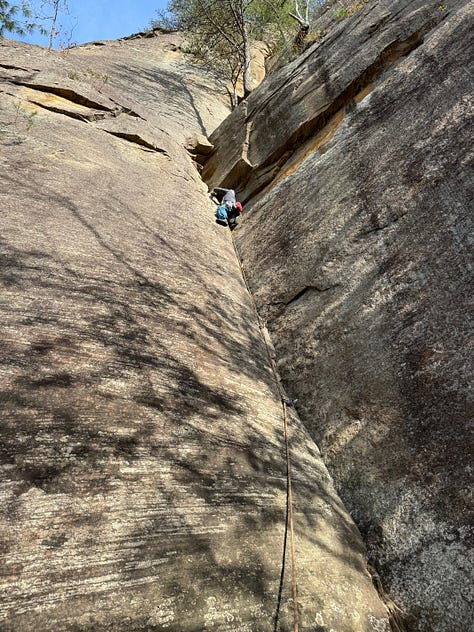

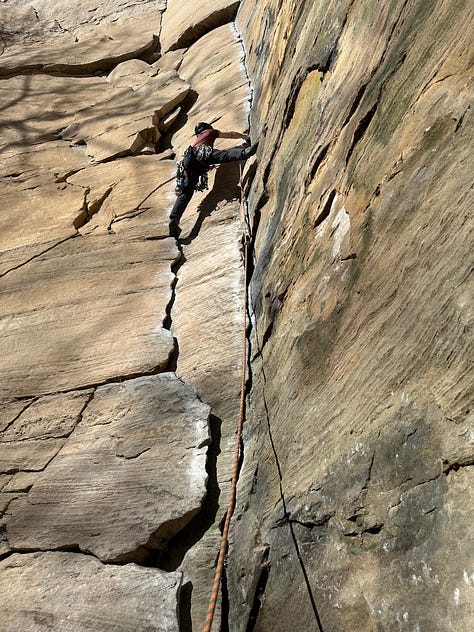

For a century, the lands in the Hudson Valley of New York that climbers call “the Gunks” were owned by one family. In the 1970s, as it passed from one generation to another, their holdings were split in three — Minnewaska State Park; the Mohonk Preserve, which is a non-profit conservancy; and the Mohonk Mountain House, which is still owned by the family that used to own all of it.

Minnewaska initially banned climbing, but, being publicly owned, pressure could be applied, and now two good-sized areas are open to climbing.

The Mohonk Preserve has always allowed — indeed, supported — climbing, and its two main cliffs are crowded with climbers, even on weekdays.

Some of the best climbing — and indeed, a good number of my favorite routes in the Gunks — are up at Skytop, the cliffs by the Mohonk Mountain House. In 1946, the hardest route in the United States might have been Minnie Belle, at Skytop, first climbed by Fritz Weissner and William Shockley (yes, that William Shockley). In 1967, one of the hardest routes in the U.S. was Foops, first free climbed by John Stannard. In 1974, the hardest route in the U.S. was Supercrack, first climbed by Steve Wunsch.

The Mohonk Mountain House used to welcome climbing, and, back in the day, before the resort became chic, a certain class of climber could afford to stay there. But in the 1990s, their calculus changed. Liability, they said, and that was probably a factor, even though the Access Fund, a climber advocacy group, offered to pay for a liability insurance rider for rock climbing. For a few years, climbing was restricted to certain times of the year and certain parts of the cliff. Then it was banned altogether.

Private ownership is a mixed bag.

There are private lands where climbing is not allowed at all — one of them is at the top of the hill on the road I live on. Local climbers have been asking for years to be allowed to climb there; the people saying no are my neighbors, only two houses down the road from me.

There are private lands where climbing is allowed with restrictions. Just the other day, someone in the Pittsburgh climbing gym told me proudly about their first multi-pitch climb. It’s a route called Roadside Attraction, in the Red River Gorge, in Kentucky. I’ve done the climb twice myself, and each time, underwent a cumbersome permitting process.

And there are private lands where climbing is embraced by private owners. Horseshoe Canyon Ranch, in Arkansas, has made a business out of climbing, camping, cabin rentals, and mountain biking. (I don’t mountain bike, but they have some spectacular-looking well-designed trails with twists and turns and jumps.)

And public ownership of climbing areas is no panacea. I mentioned in a recent post that the state authorities withdrew access to climbing at one of western Pennsylvania’s most popular areas, Lost Crag. The Access Fund is constantly fighting off proposals to restrict climbing in national parks and other federal lands. Minnewaska has still more cliffline we could climb on.

Still, when climbing is publicly owned, there are political cards climber advocates can play. Mike Lee is just lying when he says the people have no recourse.

On the other hand, when climbing is privately owned, there really is no recourse. And even when climbing seems safe in private hands — e.g., Horseshoe Canyon Ranch — circumstances or ownership can change. Climbing was allowed at Skytop until it wasn’t.

The idea that public ownership of land is antithetical to the very real need for more housing is belied by the many places — from California’s Yosemite National Park to New York’s Adirondack State Park — where private homes exist inside the park boundaries. Has Mike Lee explored the many possible compromises and collaborations between wilderness interests and housing developers?

And finally, as a practical matter, I suspect Lee is lying when he implies that public ownership of large parts of Utah costs its taxpayers money. Has he done the calculation that would balance the minuses against the pluses, the most notable of which is the jobs and money that Utah’s five national parks are responsible for? The National Park Service made an estimate of that a couple of years ago:

DENVER, Colo. – The National Park Service reports that 15.7 million visitors to Utah’s 13 national parks spent $1.9 billion in the state in 2023. That spending resulted in 26,507 jobs and had a cumulative benefit to the state economy of $3 billion.

I haven’t calculated the balance sheet either, but $3 billion buys a lot of local search-and-rescue operations.

Lee’s assertion that the national parks are mismanaged is a joke and a projection. Utah has some of the most popular parks in the U.S. (Zion was #2 last year) and the real challenge is in maintaining a balance between offering wilderness experiences that can only be enjoyed by fewer people and more sedate experiences enjoyable to many more visitors. Zion and Glacier (and soon Yosemite) have mandatory or nearly-mandatory shuttle systems to limit the number of vehicles on the roads. The most popular hike in Zion, Angels Landing, has a lottery system to limit the number of people on the trail. The most popular campgrounds in the most popular parks need to be booked six months in advance and often six months minus 10 minutes is too late; they’re all gone.

The parks need more support, and more public debate to properly balance their complex and conflicting missions. What they don’t need is to be sold off into the hands of developers who will offer the general public no experiences at all.